Whitebark Pine Conservation in the Tetons and Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

Research Associate: Nancy Bockino

Project Overview: Nancy Bockino leads a team to monitor and conserve the high elevation whitebark pine.

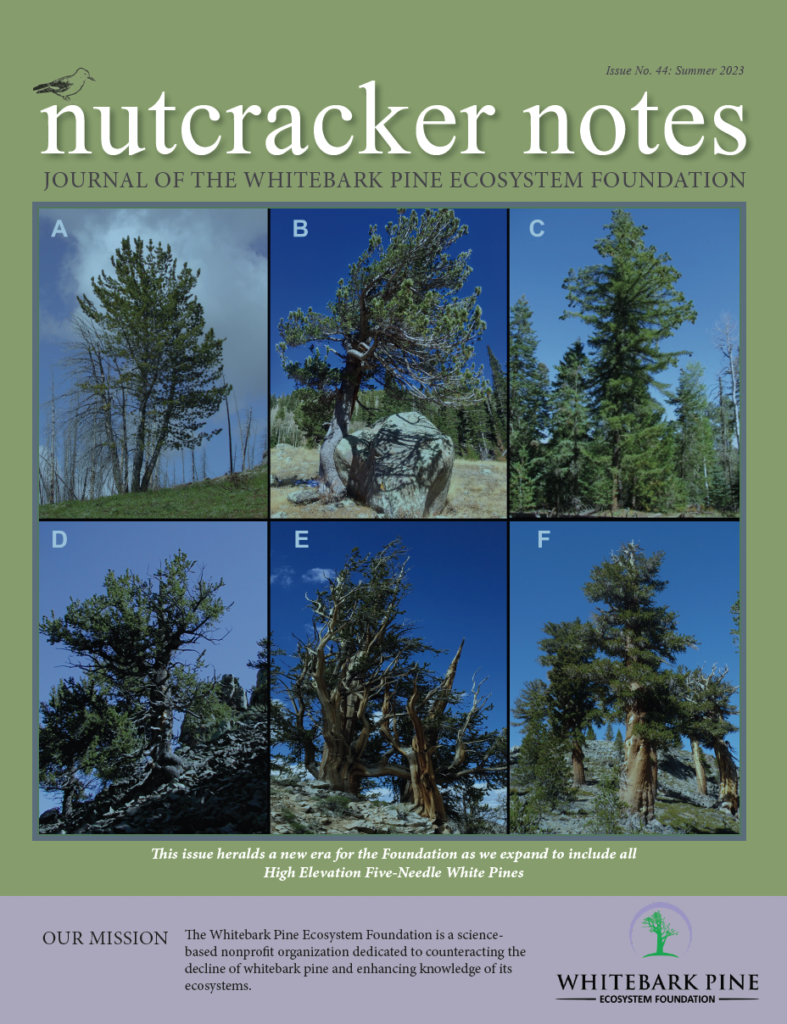

Backstory: You know those groves of trees you pass through on your way up high, near the rooftop of the Tetons? Some trees appear as a single trunk, others appear as if a handful of seeds were planted. Those are whitebark pines, a high elevation pine that catch and hold snow in the montane, subalpine and alpine ecospheres, allowing snow to slowly melt through early summer and keep the rivers running through fall. Trout and other native fish benefit from whitebarks, so do birds and mammals that eat their fatty and nutritious seeds. Stalwart and strong, they can live over a thousand years and provide habitat and protect the ecosystem higher in the mountains than any other tree. For people and animals alike, this rooftop of majestic pines not only provide oxygen to breath and clean water to drink, time spent among these charismatic and weathered trees means time spent in wild places where we fill our souls and find peace and adventure.

Whitebark pine is in grave peril. This critical species has experienced 50% overstory mortality across its range and 85% overstory mortality within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), leading to its proposed listing as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The threats to the whitebark pine include the mountain pine beetle that lays eggs in the living tissue of the tree, which has been given a huge advantage through climate change, which delays killing frosts until later in the winter when the larvae are protected by their conversion of body water to alcohol.

In addition, the whitebark pine are severely infected with an invasive fungus from Europe called white pine blister rust which was introduced into North America in the 1900s. Most trees are infected with the fungus (91% of monitoring sites in Grand Teton Park have infected trees). The fungus causes blisters on branches and the main stem, containing the spores for dispersing the fungus to new hosts. Often the stem or branch with the blisters dies off, reducing cone production, killing young whitebark and overtime killing large mature trees as well.

Current status: In partnership with Grand Teton National Park and Grand Teton National Park Foundation, NRCC Research Associate Nancy Bockino, leads a team of technicians and volunteers to conserve and study the whitebark pine in the GYE. This project advances knowledge of vulnerable alpine ecosystems by studying change in the condition of whitebark pine and high elevation vegetation by measuring and monitoring the extent of rust infection, the presence of mountain pine beetle and rates of whitebark pine mortality and recruitment. The project also directly contributes to the protection and restoration of the whitebark pine by placing pheromone packets on trees to deter beetles, and collecting blister-resistant cones, growing the seeds in nurseries, and re-planting the seedlings across the whitebark pine’s home range.

Nancy has worked on behalf of whitebark pine in the GYE for over twenty years. Grand Teton National Park’s former chief of science and resource management, Gus Smith writes, “Nancy has been the heart, soul, and engine of whitebark pine conservation in the GYE.”

Project Partners: Grand Teton National Park, Grand Teton National Park Foundation

Location: Grand Teton National Park and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

Please contact Nancy Bockino for more information: alpinelily6@hotmail.com

Read an article from Nancy Bockino and partners in the recent issue of Nutcracker Notes, the journal of the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation (Issue No. 44, Summer 2023)

Read an article from Nancy Bockino and partners in the recent issue of Nutcracker Notes, the journal of the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation (Issue No. 44, Summer 2023)

Watch the following video series to learn more about the project.

Episode 1: For the love of whitebark pine

Episode 2: What are those pouches on the trees?

Episode 3: A strangling fungus

Episode 4: Into the canopy

Episode 5: Hunting for pine cones

Episode 6: The loss of Whitebark

Episode 7: Getting to work